Hello! Welcome to the last LAN edition before reading week. October is Black History Month and to mark this, today’s LAN is Black History Month themed.

The theme for this year’s month is ‘Reclaiming Narratives.’ This was the prompt I gave to writers to inspire their writing. I opened up applications for this edition to the whole faculty, which was an exciting opportunity for everyone to contribute. I’d like to say thank you to Mina and Ben, who aren’t staff writers, for writing. You’ve brought insights to this edition - it’s much appreciated!

We have six articles, including a write up of the Law Soc Black History Month panel and an exploration of the legacy of Grenfell.

Lastly, to learn about the people on our cover, do read this article!

I do hope you take the time to read this edition.

All the best,

Jago Cahill-Patten

Publications Officer

General Section

Reflections on the Black History Month Panel

Mina Wahid

In commemorating Black History Month, we were joined by three trainees, Joshua Chima and Wesley Gyechie from Eversheds Sutherland; and Eyo Ntekim from Willkie, Farr & Gallagher, to converse about their life and experience in the corporate world.

For those who missed out on the panel (keep your eyes on the LawSoc Instagram for our next event!), here are my highlights from some questions asked that evening.

Do you feel any perceived responsibilities that make you feel like you must act as a representative for Black people? And if so, does this feed into a form of imposter syndrome?

Although the answer to this was a yes, there was a resounding emphasis on challenging this narrative, as it should not be this way. Due to underrepresentation in the corporate world, especially in more senior position, it still feels like Black lawyers are carrying the reputation for all Black lawyers and/or people on their backs. This is an unfair added pressure to the usual demands of trainee life. And whilst imposter syndrome is not unique to minority groups, Eyo mentioned the ways racist expectations can play into the narrative you have about yourself. It affects your potential and the opportunities you put yourself out for. Breaking out of this cycle is ultimately about learning to grow your confidence and building a sense of self via a fair assessment of personal achievements.

For Joshua, playing into other people’s expectations is a personal disservice. Instead, he discussed the idea of owing it yourself to be the best version of you, and letting your work speak on its own. After all, no matter how many irrational rationalisations you or other people may make about your position, you have made it so far for a reason.

What is your law firm doing to support students and solicitors from underrepresented backgrounds? And in what ways do law firms generally still fall short when it comes to DEI?

Our panellists broadly discussed the following initiatives:

Blind recruitment

Adjustments made for socially mobile talent

The 10,000 Black Interns programme

An internal Black mentorship programme starting at Wilkie this year

Such programmes show the receptivity firms have towards improving inclusivity in their intake. However, there are still ways in which law firms can open up more comfortable spaces for minority talent. For example, Joshua and Wes are the only two Black trainees in their cohort; there is a distinct drop in figures in the number of ethnic minority Partners; and generally people shy away from having conversations around race and microaggressions outside of controlled forums.

Joshua also mentioned that Eversheds had been supportive of trainees with the examinations of the new SQE, which saw a pass rate of 54%. However many other City trainees had lost their TCs following failure to pass the first exam. There needs to be an interrogation of these numbers, and explanations for the patterns behind them. Only then can firms truly start to implement support systems aimed at elevating underrepresented groups.

What advice would you give to aspiring Black solicitors?

In the words of Eyo, work as hard as you need to, to get to where you want to be.

There is no substitute for hard work and be shameless in aspiring to achieve your ambition. Even if this means becoming a LinkedIn Warrior… Generally, there are a lot of people in the spaces you want to be who actively want to help underrepresented groups break into the legal sector. According to Wes, stay curious, confident and seek out opportunities. Reaching out for events and networking will slowly but surely pay off.

What does Black History Month mean to you?

Finally, to wrap up, Black History Month is not only a celebration of the progress Black people have made, but also a time to recognise the work still to be done. From Eyo, “the fact that there is a Black History Month is an indication of where we still have to go.”

The Legacy of Grenfell is More Equal and Safer Housing

Ben van Meggelen

On the 14th June 2017, the nation was shocked by the Grenfell Tower fire tragedy, which claimed the lives of 72 people and displaced hundreds more. The fire’s rapid spread was in large part possible due to the building’s flammable cladding, which had been installed despite known fire safety risks. Many residents had previously raised concerns about the building’s safety, but their voices were repeatedly ignored by local authorities. This negligence echoed a history of racial and socio-economic discrimination that has affected minority communities in Britain for decades as Grenfell Tower was a council housing project, with many inhabitants stemming from the Black, Asian, and minority ethnic communities (BAME). Minority groups being disproportionately affected by incidents such as the Grenfell Tower fire is a natural result of systematic economic disparities in the UK. This serves as a significant hurdle to homeownership.

This incident served as a stark reminder that there is still a lot of progress required in the housing sector to achieve equality, even if racism in its most obvious form was addressed by the pivotal changing point of the Race Relations Act 1976. This prohibits discrimination in employment, housing, and the provision of services. The Act also established the Commission for Racial Equality, which signals a commitment to addressing racial disparities. However, despite these legislative advances, structural inequalities have persisted. Grenfell serves as a drastic wake-up call as the issues which caused it were not new or previously unknown. Before Grenfell, minority communities in Britain were already disproportionately represented in substandard social housing, often living in conditions that posed health and safety risks. Therefore, the Grenfell tragedy is yet another reminder that housing laws and protections for tenants have failed to keep pace with current living realities, leaving vulnerable communities exposed.

As a result of the Grenfell fire, the British government initiated a public inquiry to identify systemic failures, which need to be urgently addressed to combat discrimination in all of its shapes and forms. This inquiry has led to a series of legal and regulatory reforms, which aim to improve building safety standards and tenant rights, particularly in the context of council housing. One of the most significant outcomes of the inquiry was the Fire Safety Act 2021 which aimed to strengthen fire safety standards across high-rise buildings, particularly those in the social housing sector. This law clarified responsibilities for building safety, including the requirement for proper assessment and maintenance of cladding materials; a direct response to the Grenfell fire. Further, the Building Safety Act 2022 was introduced, which addresses the loopholes that had allowed unsafe building materials to be used in residential structures. The Act mandates stricter safety checks, greater transparency about building materials, and clearer responsibilities for building owners and landlords. Additionally, the Social Housing (Regulation) Bill introduced in 2023 aimed to empower tenants by ensuring their safety concerns are taken seriously by authorities and landlords. The bill includes provisions for a stronger regulatory body with enforcement powers to ensure landlords meet their obligations for safe and dignified living conditions.

In summary, the Grenfell tragedy and its aftermath highlighted that while the legal reforms represent necessary steps towards safer housing, it is insufficient without tackling the root causes of inequality as well. The incident underscores the need for greater vigilance and accountability in protecting all residents, regardless of their race or economic status. As the nation remembers the lives that were lost, there is a collective call to honour their memory by ensuring that such an event never happens again; and that minority voices will not be overheard or blatantly ignored any longer.

Controlling the Narrative: Britain’s Reluctance to Talk about the Slave Trade

Mia Ramage

Whilst the UK Prime Minister and monarch were present at the 2024 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting held in Samoa this month, there was one noticeable absence: any willingness to offer an apology for Britain’s involvement in the Transatlantic slave trade.

10 Downing Street announced a week ahead of the summit that there would be no apology issued by King Charles III (the head of the Commonwealth) on behalf of the United Kingdom, and no discussion of reparations. His opening speech on the 25th October lauded the Commonwealth Meeting as an open forum to “discuss the most challenging issues with openness and respect”- that is, of course, as long as that discussion does not need to be followed by an apology.

The approach taken by the UK is hollow, but unsurprising. Starmer’s response seems to echo that of former Prime Minister Sunak’s remarks last year, with Sunak and Starmer both projecting a desire to look to the future, rather than unpicking a messy, colonial history. The line taken by the government is a hard pill to swallow when King Charles’s speech, which must reflect the stance of the current government, itself notes how “the most painful aspects of our past continue to resonate.”

In emphasising an approach that looks only to future growth, it seems that Britain’s colonial past should be ignored, swept under the proverbial rug as being confined to a bad time in history. Except that these painful aspects of Britain’s culpability in the transatlantic slave trade do continue to resonate, and so it is hard to reconcile this fact with the UK Government’s complete adversity to apologise for their part. Reparations are off the table, as long as those reparations are intended for the countries affected. The government doesn’t seem to be as willing to take such a forward-facing view when it comes to reparations to slaveowners which, thanks to the conditions in the passage of the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, were still being paid from taxpayers’ money until as late as 2015. None of this £20 million payout (now estimated to be worth around £2.4 billion) went towards those kept as slaves.

With reparation debts for the UK estimated to be around £18 trillion, it’s not hard to see why the government is reluctant to pay such a debt, and so eager to keep discussions of it off the table. Yet the 300 years of brutalities and atrocities of the slave trade are not so easy to hide from, and the continued effect on former colonies and countries cannot be confined to a thing of the past. Britain may want to forgo culpability by refusing to apologise, but their silence is damning, and cannot be made to go away by remaining quiet. Despite the UK’s reluctance, the need for reparations was a theme emphasised at the biennial Commonwealth Meeting, with an agreement being reached that it is finally time for the discussions to be had over reparatory justice. In whatever form it takes, the conclusion of the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting seems to hold a tentative promise that the UK government will no longer control the narrative on the needs for reparation.

Chagos Islands: The Final Chapter in British Colonial History

Aykhan Allahveranov

Following a five-decade dispute, the UK government finally agreed to hand back the Chagos Islands, an archipelago located in the Indian Ocean, to the southeast African island country of Mauritius.

Back in 1965, in splitting the Islands from Mauritius, the UK expelled between 1,500 and 2,000 islanders. This was to lease Diego Garcia, the largest of the Chagos Islands, to the United States for military use, which the two allies have since operated jointly.

The ensuing fifty years of legal and political wranglings finally came to fruition when early this month, it was announced that the negotiations on the exercise of sovereignty over the British Indian Ocean Territory were concluded. A programme of resettlement by the Mauritian government on the islands is forthcoming.

The role of international law was instrumental. Following a series of unsuccessful legal challenges against the UK’s control of Chagos, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued a non-binding advisory opinion in 2019 in favour of Mauritius. The UK had wrongfully forced the inhabitants of the island to leave to make way for a US airbase and, hence, should give up its control of Chagos, the ICJ said. To put political pressure on the UK, the UN General Assembly voted in favour of a resolution stating that the UK should give up the Chagos within six months. As if this was not enough, the ruling by the ICJ was confirmed two years later by the UN’s International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. However, the UK government remained silent. Only in 2020 did Liz Truss, in her capacity as the Prime Minister, begin talks with the Mauritian government.

Just as important as the role of law, has been the role of politics. The geopolitical landscape had changed between 1965 and 2022. It is this change that can explain the efforts by the British government to finally complete its decolonisation. In a world of weakening democracies and rising multipolarity, claiming to be a beacon of rule of law and democracy was incompatible with the continuing occupation of the archipelago. The charge of double standards was no longer sustainable. Therefore, the main goal of Britain was to bring itself into “alignment with international law,” writes one professor.

While negotiations are complete, an international treaty will need to be drawn up. The deal is, however, unlikely to fall through. As ratification of treaties does not require a parliamentary vote in the House of Commons, there is no reason why this cannot be done quickly.

Commercial Awareness Section

Regulatory Remedies:

This term refers to the corrective measures government authorities impose to address and rectify anti-competitive conduct by corporations, who are mandated to respond accordingly in order to continue with their proposed plans. In the UK, the CMA is the principal authority responsible for imposing these, as they did when presented with the Vodaphone-Three merger. Such remedies are crucial for maintaining market integrity, protecting consumer welfare, and ensuring fair competition. The Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024 expanded the CMA’s powers to impose considerable fines for breaching antitrust laws, however they have limited ability to do so for procedural breaches. Typically, remedies fall into three categories: structural, behavioural, and conduct-based. Structural remedies may involve breaking up monopolistic entities or requiring divestitures to prevent undue market dominance. Behavioural remedies impose specific obligations such as mandating transparent pricing practices or restricting exclusive agreements that limit competition. Conduct-based remedies directly target damaging behaviours like price-fixing or collusion. These measures are instrumental in preventing market abuses and ensuring that anti-trust laws operate efficiently.

Iman Khalil

CMA Casts Doubt on Vodafone-Three Joint Venture, Citing Fears of Higher Mobile Costs and Reduced Competition in the UK Market

Matthew Wang

All eyes are on the highly anticipated joint venture between Vodafone UK and Three UK, as their merged entity could become the largest mobile operator in the UK.

Following a 5-month investigation, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) published its Provisional Findings Report. They found that the joint venture would lead to a substantial lessening of competition (SLC) by out-competing the 2 other main network operators, BT/EE and Virgin Media O2. The joint venture would remove the “competitive constraint” between Vodafone and Three, increasing the price of mobile telecommunications services (or decreasing data packages), and customers would likely bear additional costs for improvements in mobile services.

Moreover, this price increase would affect mobile virtual network operators (MVNOs) such as Sky Mobile, Lyca, and Lebara, who rely on wholesale access to Vodafone and Three’s networks for their services.

Vodafone and Three contended that, conversely, the merger could “unleash more competition” and fix the UK’s “dysfunctional mobile market.” Furthermore, that BTEE and VMO2 were “clear market leaders, acting as strong competitive constraints.”

“Overstated”

The CMA believes such submissions and claims of superior network quality to be “overstated”; the merged entity’s enormous market power would disincentivise them to improve their 5G network.

The CMA UK population survey found price to be the customer’s main consideration for choosing their mobile service provider. However, their Merger Simulation found that the merged entity would increase mobile services price by £13.04 and £9.76 for the average Three and Vodafone user respectively. Additionally, the diagram below depicts a 1.5% decrease in consumer welfare, especially hitting low-income subscribers who are more price sensitive.

In deciding remedies, the CMA must find a reasonable and practical solution that is the least costly and instructive, and proportionate to the SLC. Possible structural remedies include, divesting certain mobile network assets; increasing the competitiveness of MVNOs; allowing new mobile service providers to enter the market (“Partial Divestiture Remedy”); or prohibiting the merger completely. This is a low-risk way of preventing the SLC. This was preferred over behavioural remedies, such as making Vodafone and Three deliver network investments in a joint business plan (“Investment Commitment”); extending existing customers’ contract terms; and ring-fencing part of the merged entity’s capacity exclusively for MVNOs.

At Slaughter and May, partner Victoria MacDuff (counsel for Vodafone), said that the “joint venture agreement [was a] bit like a prenup.” Vodafone and Three’s priority was determining how the merger would benefit customers; this requires the legal team at Slaughter to look at the joint venture in the long term and consider its lifespan and evolving terms.

An “unprecedented remedy package”

The companies responded to the CMA’s provisional findings, allaying the CMA’s fear of price increases, by proposing to maintain tariffs at a maximum of £10 for 3UK’s “value-focused” customers, social tariffs, and protections to registered vulnerable customers for 2 years. More generally, the CEO of Vodafone, Margherita Della Valle, asserted that there were no plans to change pricing strategies. Moreover, both companies said the merged entity would offer a 3-year plan to MVNOs with 2.5m or fewer customers based on pre-agreed terms, and further agreed to a sale of spectrum to Virgin Media O2.

This demonstrates their willingness to comply with CMA recommendations, according to Matthew Howett, CEO of Assembly Research. However, Tom Smith, competition lawyer at Geradin Partners, warned that this “unprecedented remedy package” does not eliminate the chance of CMA blocking the merger if remedies were deemed ineffective.

Minority investment:

Sometimes referred to as a non-controlling interest, a minority investment refers to ownership of less than 50% of a company’s equity. The implication of this is that the founder or majority shareholder, also known as the parent company, retains control over its management. Generally, minority investments are valued between 10-30%, and are predominantly taken on by venture capital or growth equity firms. As these firms tend to invest in startup companies which they believe are already well directed and headed for rapid growth, they are well suited to be minority investors. Naturally therefore, minority investments are mutually beneficial, as it allows the founders/ parent company to continue to operate without external interference. Additionally, the minority stakeholder isn’t burdened by unwanted managerial responsibilities but can still reap economic rewards. This is not to say that a minority investor is completely impotent when it comes to executive decisions, as they are still involved in discourse surrounding the company’s operation and can advise the majority. They also have certain protected rights under the Companies Act 2006, for instance tag-along rights when a sale is proposed.

Iman Khalil

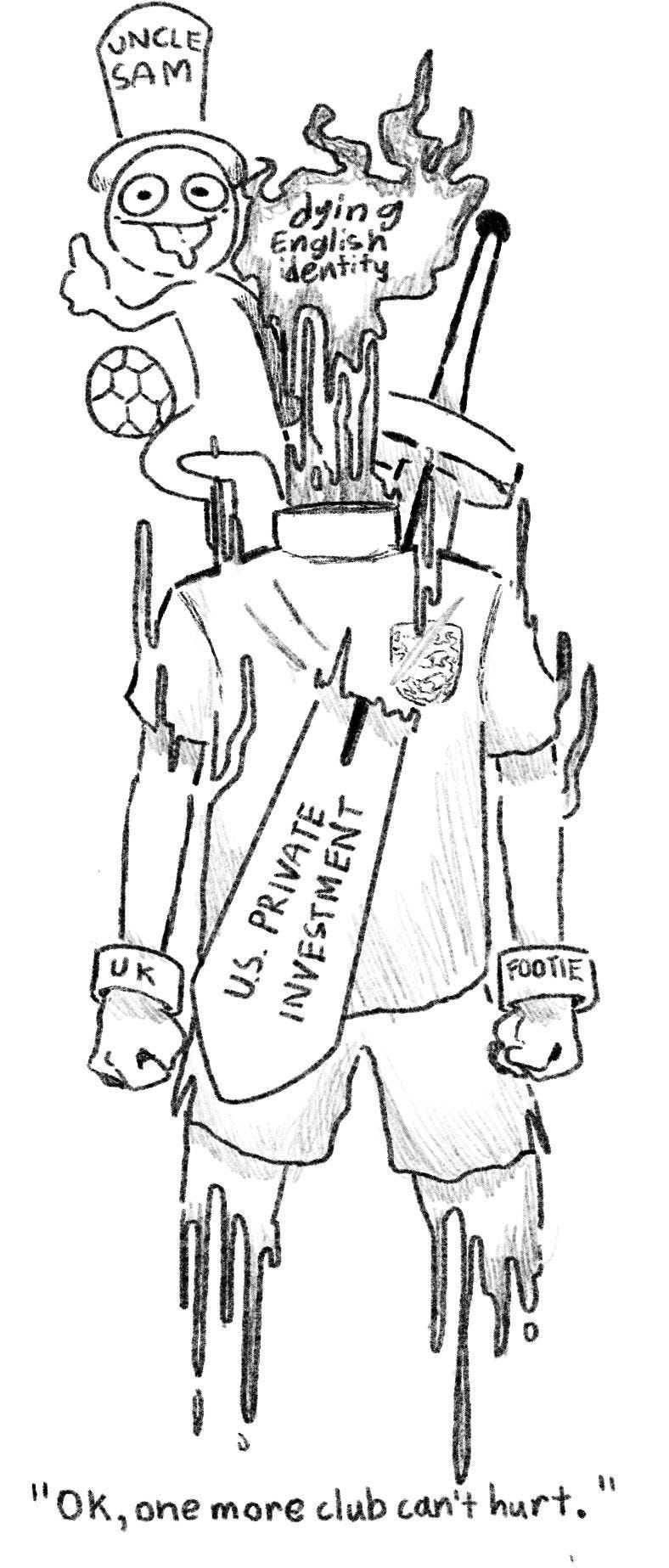

Pitch Invasion: The US Takeover of English Football

Adrien Charles

Reports have emerged that an American consortium is in takeover talks with Championship club Sheffield United, marking the latest chapter in the growing trend of American private investments firms acquiring English football clubs. This development invites a closer look into the unique benefits and challenges US investors face in navigating the unpredictable landscape of English football.

Background

Whilst ownership in the highly lucrative English Premier League has historically spanned Russian oligarchs, Gulf sovereign wealth funds, and major Chinese conglomerates, American investors have increasingly positioned themselves as the primary contenders. This influence has trickled down into the lower tiers of English football, with over a third of the 92 professional teams in England’s top four leagues now having some form of American ownership – with the majority being private investment firms (i.e. private equity firms, sports management groups.)

The Payoff of Buying into English Football

While the prices being paid for football clubs across England have reached record levels, they are still seen as cheap investments in comparison with American sports franchises. Securing the rights to the latest US Major League Soccer franchise – San Diego FC – required a $500 million investment from a consortium headed by Egyptian billionaire Mohamed Monsour. In contrast, English football clubs with historic legacies, dedicated fan bases, and international reach are available at a fraction of that cost, making them particularly attractive to US private investment firms.

This appeal is amplified by the potential for significant commercial upside through promotion within the English football league system. Unlike American sports, where teams remain in the league regardless of performance, English football offers a promotion and relegation model that can provide sizeable commercial rewards for teams that ascend through the ranks. Success on the field translates directly into higher revenues from broadcasting rights, sponsorships, and match-day earnings, which heightens the investment's value.

In sum, the chance to acquire storied clubs with high-growth potential at relatively modest prices, make these investments increasingly irresistible for American private investment firms.

Potential Pitfalls of Club Ownership

The trend of financing English football club acquisitions with complex debt instruments carries serious risks, particularly given the volatility of promotion and relegation. A notable example is ALK Capital’s purchase of Burnley. In 2020, the American investment firm acquired the club through a leveraged buyout, taking out a sizeable loan from MSG Holdings and also using the club’s own money as collateral. This means that a drop to a lower league not only reduces broadcasting and match day revenue but also intensifies pressure to service the debt incurred during the acquisition.

Furthermore, the strategy raises questions about the motives of investors who may prioritise short-term financial gains over the club’s long-term health and community ties. English football clubs have a unique connection to their local communities and fan bases, which can result in heightened scrutiny and accountability for investors. Fans are far more vocal and less patient than traditional shareholders, with a keen awareness of ownership decisions and a strong desire to see the club’s values upheld. For example, in January, the co-founder of Pacific Media Group was confronted by supporters of Belgian club KV Oostende in a restroom, with fans holding him responsible for the team’s decline since its acquisition by the firm.

Looking Ahead: The Future of American Investment in Football

The American takeover of English football shows no signs of slowing down. American private investment firms are also likely setting their sights on other European football leagues, with clubs like Lyon in France’s Ligue 1 and AC Milan in Italy’s Seria A already under American private equity ownership. However, expanding into other leagues may not prove as rewarding as it is has in England. In Germany’s top league, the Bundesliga, ownership rules prevent commercial investors from holding more than 49% of voting shares in any club, ensuring fans retain co-ownership and influence over strategic decisions. For private investment firms, buying into a club but not getting the power to freely make decisions, represents a very unattractive model for those seeking control over financial strategy, operational direction, and long-term club management.

Links to More Articles:

Iman Khalil

Michael Kors owner Capri’s shares crater after $8.5bn merger blocked

Judge Rochon has ruled against the proposed merger between Capri and Tapestry, a decision welcomed by the FTC—the U.S. equivalent of the CMA. Central to the ruling were concerns that the merger would grant the combined fashion powerhouses a 59% market share, breaching antitrust principles. This decision reflects the growing regulatory scrutiny facing the fashion industry regarding market consolidation and competition.

Poland’s stock market has a hot new entrant

Poland’s most popular convenience store Zabka has launched its IPO, and it’s expected to revive the struggling Warsaw Stock Exchange. As a result of Donald Tusk’s government reforming the state pension system in 2013, the market capitalization of companies listed on the WSE dropped to 26%, and Polish companies subsequently chose to raise funds elsewhere. It is hoped that now Zabka has put their faith into the WSE, other large corporations will follow suit.

BlackRock wants to talk about retirement. Climate, not so much

Under fire from U.S. conservatives, BlackRock has largely abandoned its ESG agenda, shifting focus to retirement and infrastructure while downplaying climate commitments. CEO Larry Fink’s latest communications emphasised retirement products over sustainability, likely in an attempt to restore political favour. Though BlackRock still offers sustainable investments, its support for environmental shareholder proposals has plummeted, signalling a pivot driven more by political pressures than by principle.

‘We Are Returning Your Crypto Tax’ – UAE announces bold tax moves

The UAE has announced its revolutionary decision to eliminate VAT on cryptocurrency transactions starting November 15, 2024, and will retroactively refund VAT paid since January 1, 2018, marking a significant boost for crypto businesses and investors. This is part of its broader strategy to establish itself as a leading global hub for digital assets and attract both local and international investments.